TEEN Snapshot — September 2025

Bridging the Empathy Gap–How Storytellers Can Capture Adolescent Audiences & Influence Perceptions of Systems-Facing Youth

Through this original research series, CSS elevates youth voices and generates up-to-date, actionable, and thought-provoking research insights for storytellers seeking to authentically represent, positively impact, and capture the attention of young audiences. Learn more here.

Key Takeaways

There are More Systems-Facing Youth Than You Think:

Around 1 in 4 (24.7%) adolescents are systems-facing

Over 2 in 5 (41.8%) adolescents have a friend or relative around their age who is systems-facing

Media Can Bridge the Empathy Gap:

Personal connections combined with educational exposure to systems-facing youth increased empathy by over 35%

Indirect exposure–like good media representation–can increase empathy among adolescents with or without real-life exposure

More Representation Wanted:

Over 60% of teens who know systems-facing youth IRL want more media representation

The Center for Scholars & Storytellers (CSS) at UCLA has conducted new research on how adolescents perceive systems-facing youth and what entertainment media could do to better serve them.

“Systems-facing youth” = young people who have experience with any of the following systems:

Systems-facing youth make up a sizable portion of young people in the US.

At the same time, hundreds of thousands of children interact with the foster care system. On any given day, between 368,000 and 390,000 children are in foster care, with more than 600,000 served annually.

More than 1.6 million U.S. youth are processed by the juvenile justice system annually and youth of color are disproportionately represented. While Black youth comprise 17% of the 10-17 year old population, they make up more than double the percentage of juvenile arrests.

Immigration status also shapes the experiences of many young people. As of 2023, there were approximately 1.5 million children under age 18 who were unauthorized immigrants (i.e., undocumented minors) living in the United States.

These categories often overlap—youth who have been in foster care are more likely to experience homelessness, and unhoused youth often encounter both the criminal justice and child welfare systems. Based on these statistics, we’ve estimated that roughly 15% to 25% of adolescents (ages 10-25) in the US are systems-facing. Although many young people interact with and are impacted by systems–they remain under- and misrepresented in our media landscape as problems and charity cases.

At CSS, we know that media plays a powerful role in shaping how young people perceive and understand stigmatized and marginalized communities. Media can bridge social distance, foster empathy, and give voice to a population that is too often stigmatized or silenced. The entertainment industry has an unparalleled opportunity to tell more accurate, nuanced, and compassionate stories about systems-facing youth — creators can help challenge stereotypes, build public understanding, and create a future with more equity and opportunity for those impacted.

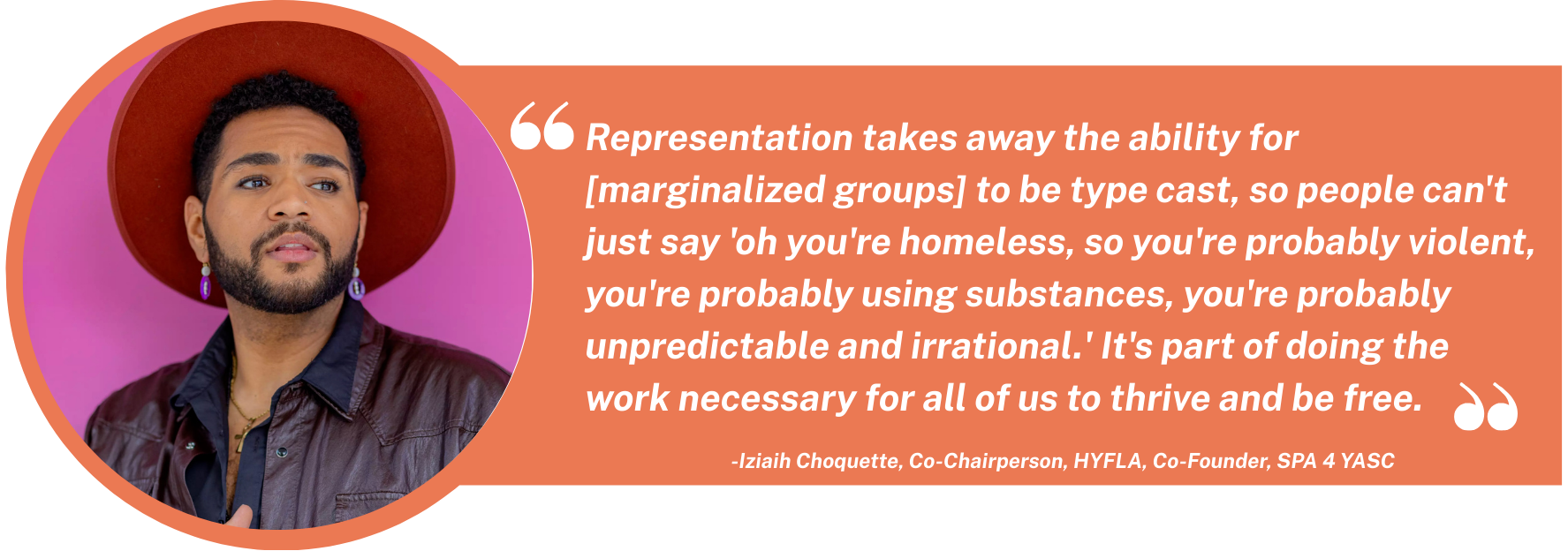

At our recent convening, Evolving Depictions of Systems-Facing Youth in Media, we brought together advocates, researchers, entertainment professionals, and youth with lived systems-facing experience to co-create solutions for advancing authentic representation. Youth participants shared firsthand insights about the impact of media portrayals—both the harm caused by stereotypes and the potential of authentic stories to shift how they see themselves as well as how society perceives them.

This study builds on CSS’s previous research that underscores the importance of authentic and accurate representations of systems-facing youth. Our study on foster care representation in the popular film Instant Family, for example, highlighted a critical gap in understanding and perception of the foster care system between young people with lived foster care experience and those without.

Three reasons why empathy matters:

It can lead to lower prejudice against systems-facing youth

It motivates people to do more to help

It helps empower systems-facing youth to see themselves differently

This finding suggests that exposure can lead to curiosity and a desire to better understand their peers with different backgrounds and lived experiences than their own.

Youth with first-hand foster care experience were 3.43 times more likely to believe the portrayal of foster youth and foster care in the movie Instant Family was accurate compared to youth with no first-hand foster care experience. Click here to learn more.

To deepen this work, CSS designed a national survey of 1,552 adolescents ages 10 to 24 to better understand how exposure (or lack thereof) to systems-facing youth influences adolescents’ perceptions of and empathy toward these young people.

We found that a significant proportion of our respondents were systems-facing themselves (24.7%) and, in general, most adolescents have some level of high quality exposure to systems and systems-facing youth in their real lives–meaning they have a friend or family member around their age who is systems-facing (41.8%), or they have learned about systems in educational environments (53.7%).

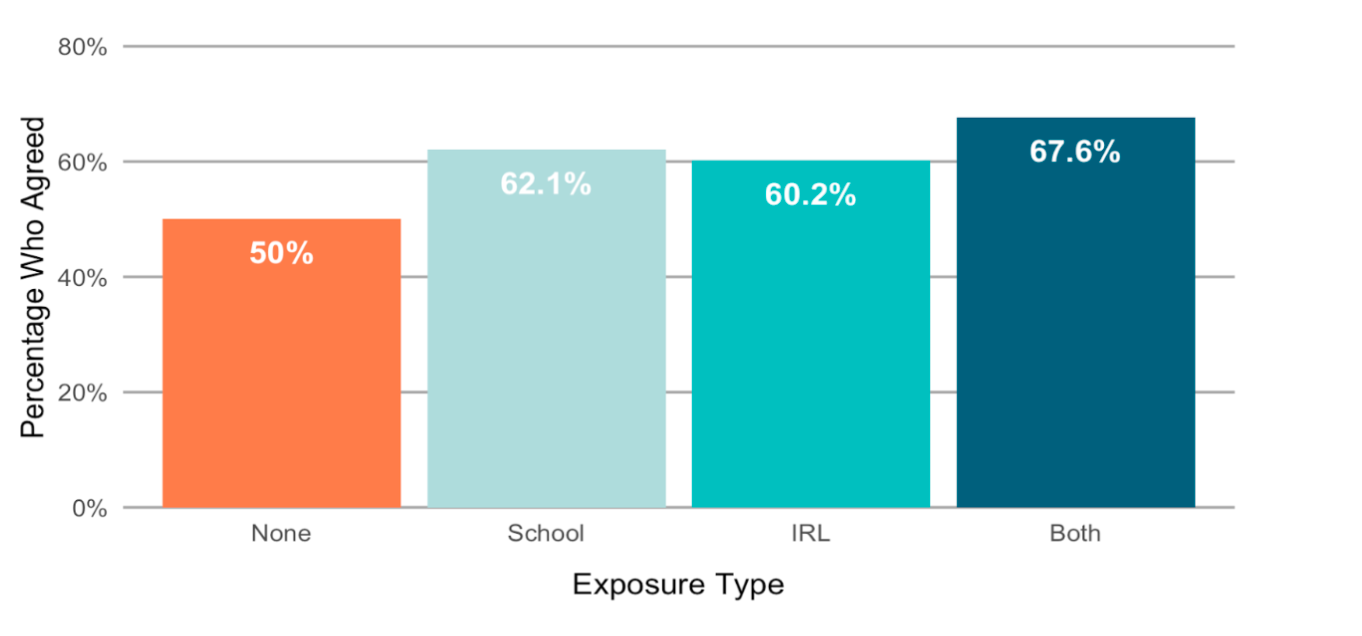

We also found that high quality exposure to systems-facing youth fosters greater empathy for these groups. Adolescents who reported some level of high quality exposure, especially those who had both a personal connection and had learned about systems in educational environments, were more than 35% more likely* to view systems-facing youth as victims of circumstance and to believe that society should do more to support them.

Through this research snapshot, we seek to highlight that media can bridge social distance, foster empathy, and give voice to a population that is too often stigmatized or silenced. The entertainment industry has a significant opportunity to shift narratives. By telling more accurate, nuanced, and compassionate stories about systems-facing youth, creators can help challenge stereotypes, build public understanding, and foster empathy.

High-Quality Exposure to Systems-Facing Youth Drives Empathy

To better understand how young people think about systems-facing youth and how exposure contributes to that, we asked participants two questions to measure empathy. Specifically, we asked to what extent respondents agreed or disagreed with the idea that systems-facing youth are victims of circumstance, and to what extent society does enough to help them*.

We then analyzed the responses by exposure type. We compared levels of empathy across three different groups*:

(1) those who have a friend or family member around their age who is systems-facing

(2) those who had only learned about one or more of the systems through school or a community program and,

(3) those who have had neither a personal connection or educational exposure to systems-facing youth*.

We found that adolescents who reported having personal connections to systems-facing youth were more likely to have empathy for these young people than adolescents with no exposure*.

-

1 Adolescents with both personal and educational exposure were more likely to agree that society should do more for systems-facing youth (67.6% vs. 50.0% with no exposure, a 35.2% relative increase) and that these youth are ‘victims of circumstance’ (63.9% vs. 45.2%, a 41.3% relative increase).

2 To assess adolescents’ empathy toward systems-facing youth, our survey adapted these 2 questions from a validated measure of empathy that has been widely applied in studies measuring empathy across different populations.

3 For this report, we consider and refer to the first two groups as having “high-quality exposure” to systems-facing youth.

High-quality exposure leads more adolescents to view systems-facing youth as “victims of circumstance”:

-

4 For each of these groups, we measured exposure and empathy related to each system and then averaged across all four systems.

5 All survey participants were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “[Group] are victims of circumstance” and “Our society does not do enough to help [group]” for four groups of young people—those who are unhoused, incarcerated, in foster care, or immigrants. They could answer on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. For analysis, we focused on the percentage of respondents who chose agree or strongly agree for each group. We then averaged those percentages across the four groups to create an overall score that reflects perceptions of systems-facing youth as a whole.

High-quality exposure also leads more adolescents to believe that “society should do more” for systems-facing youth:

Although introducing more young people to systems-facing youth is not a scalable solution to bridge the empathy gap, these findings also show that indirect exposure has a surprisingly similar influence on empathy. Adolescents who had learned about at least one of these systems through school or community programs also expressed more empathy for systems-facing youth than those with no exposure. And, their empathy levels were comparable to those who have personal connections with systems-facing youth, indicating that both direct and indirect high-quality exposure to systems-facing youth can positively influence adolescents’ attitudes and perceptions.

BRIDGE THE EMPATHY GAP:

In fact, we found that indirect exposure further increased empathy, even for those respondents who already had a personal connection. As illustrated in the graphs below, respondents who had personal connections to systems-facing youth and had learned about systems in educational environments were nearly 35% more likely to agree that society should do more to help systems-facing youth and to believe that systems-facing youth are victims of circumstance.

The empathy gap between adolescents with high-quality exposure to systems-facing youth and those without it presents an opportunity for storytellers to rewrite the narrative on this population.

This finding is consistent with the personal accounts shared by systems-facing youth at our 2025 convening, who expressed that narrative stories can change how they see themselves–and speaks to the impact that learning about systems can have on everyone.

Respondents with both types of high quality exposure to systems-facing youth were 35.2% more likely to believe society doesn’t do enough to help these young people.

of respondents agree incarcerated youth are victims of circumstance

of respondents agree foster youth are victims of circumstance

Respondents with both types of high-quality exposure to systems-facing youth were over 40% (41.3%) more likely to view systems-facing youth as victims of circumstance.

Young Audiences Are Calling for Real Stories of Systems-Facing Youth on Screen

There is a disparity between the lack of representation (or misrepresentation) of systems-facing youth in the current media landscape and the demand for more media representation from the many youth who know systems-facing youth or are systems-facing themselves. Onscreen portrayals do not reflect the sheer numbers of this population and when they are seen, they are often the problem or charity case rather than a multi-faceted individual, with resilience, agency, and joy.

In all, over 40% of our respondents had a personal connection to a young person around their age who is systems-facing or have learned about systems in educational environments. Of this group, over 60% (61.6%) reported that they want to see more content depicting real stories of systems-facing youth.

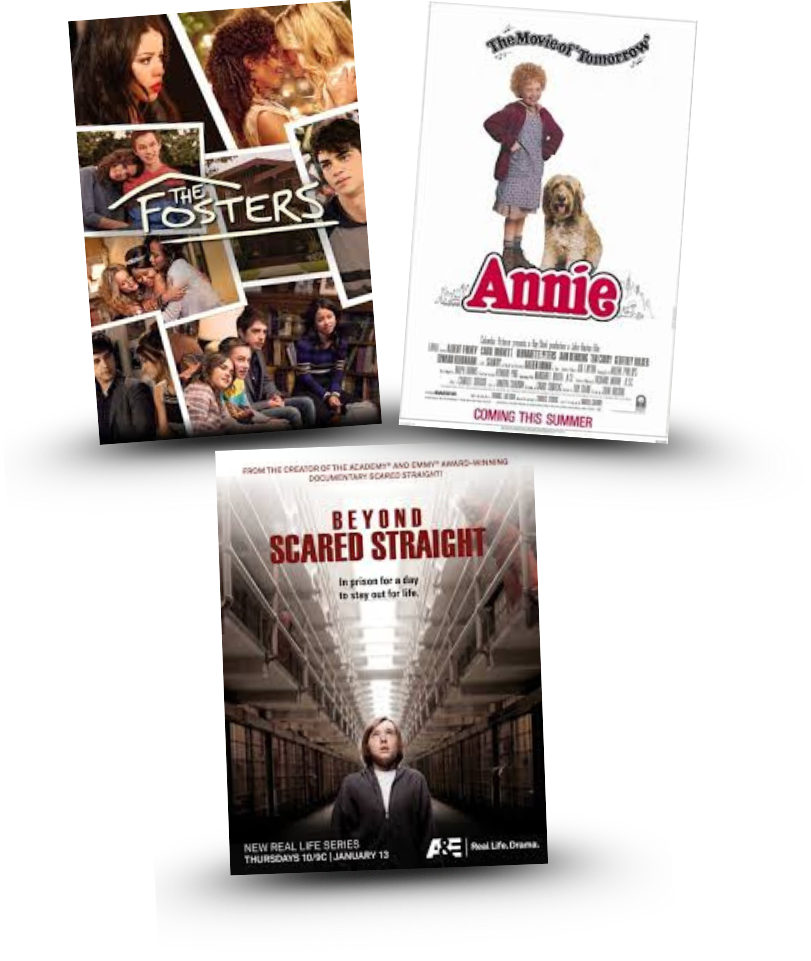

However, many young people who know systems-facing youth or are systems-facing themselves rarely see them represented authentically on screen, and when they do, the portrayals are often either harmful or misleading. For example, media depictions of criminal justice-system-involved youth frequently lean on stereotypes that paint them as dangerous or untrustworthy, and reinforce negative views about these young people. Research also shows that films depicting the foster care system tend to exaggerate or overrepresent themes like psychological and behavioral issues among young people placed in foster care or drug-addicted parental figures, creating distorted public perceptions of what foster care actually looks like and how young people move through and interact with this system.

Research has shown that counterstereotypical representations in media, meaning stories that depict people in ways that defy or complicate stereotypes, can play an important role in reducing unconscious bias. Counterstereotypical portrayals can disrupt automatic associations, lead viewers to question preconceived notions, and foster more inclusive attitudes. When storytellers create characters and storylines that push back against stereotypes, they can dismantle deep-seated biases among audiences.

At the same time, whole groups of systems-facing youth are missing from mainstream narratives altogether. Studies have shown that migrant and racialized youth often face overlapping challenges with child welfare, criminal justice, and immigration systems—yet their experiences remain largely invisible in TV and film. Similarly, young people experiencing homelessness—who are disproportionately LGBTQ+ and youth of color—rarely see authentic portrayals of their struggles or resilience.

Authentic, humanizing portrayals of systems-facing youth have the power to shift how audiences understand the systems themselves. Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us is a powerful and, unfortunately, rare example: by telling the individual stories of the five boys wrongfully accused in the Central Park case, the series moved millions of viewers to see beyond headlines and stereotypes, sparking widespread conversation about systemic racism and injustice.

Our research has consistently shown that young people want to see stories that reflect real experiences and identities on screen, and that authentic, inclusive storytelling not only resonates with youth but also benefits the bottom line—films and shows with higher authenticity scores tend to perform better with critics, audiences, and at the box office.

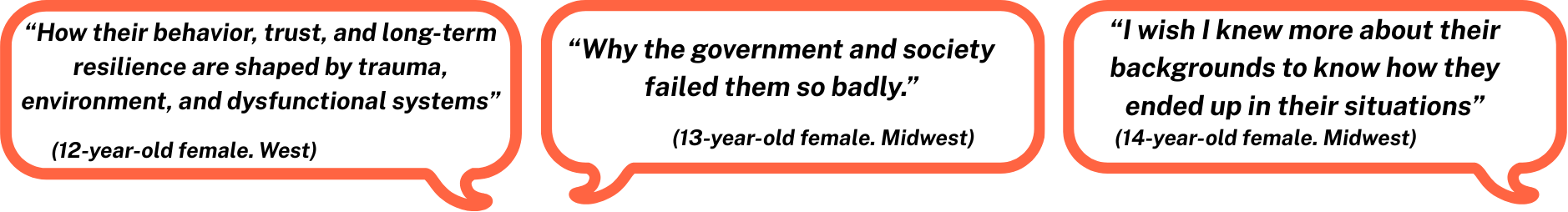

When asked what they wished they better understood about systems-facing youth, respondents revealed a deep curiosity and desire for greater understanding of systems-facing youth—particularly around how and why young people enter these systems, what daily life looks like for them, and what the long-term impacts are. At the heart of their responses is both empathy and frustration: many of our respondents reported that they want to understand:

the structural and systemic factors that shape these experiences, such as racial bias, trauma, and systemic failures, as well as the barriers that make it difficult to leave these situations.

what role they or society as a whole can play in providing meaningful support to systems-facing youth and preventing further harm.

We also asked respondents what they wish they understood about systems-facing youth.

Conclusion

For storytellers, these insights present a clear call to action. Film & television shapes how systems-facing youth see themselves — and also influence how they are perceived by others. Life changing and eminently watchable portrayals are easily achieved by working with advocacy and lived experts who can facilitate workshops, offer script reviews, and provide thought starters wherever a creative is in their storytelling process.

Modern examples like the series Pose and the film Instant Family have been praised for their authenticity and impact. Pose brought attention to unhoused youth, especially queer and trans individuals who are often forced into survival because of rejection, poverty, and systemic failure. The show increased trans and HIV positive representation and earned four Emmy Awards. Instant Family, based on a true story, helped audiences connect with the realities of foster care while celebrating the strength of the children and families involved. More recently, the series Will Trent, about a former foster youth turned lawyer, has found success but remains one of the few current shows tackling these issues. With older trailblazing series like The Fosters fading from the spotlight, there is a clear gap that can be filled by the industry, ensuring more viewership in and critical acclaim.

When people with lived systems-facing experience are included and centered, their stories can inspire fresh narratives that shift perception, build empathy, and encourage public support for policies and civic initiatives that forever improve lives and outcomes. We hope this research continues to advance the power of media to spark meaningful and lasting impact.

Additional Resources

LA-based Organizations that Support Systems-Facing Youth

Check out, if you are able to support, these organizations that do important work in the LA region:

Authors

-

Alisha J. Hines, PhD

VP of Research & Programs

As director of research, Dr. Alisha J. Hines leads the research team and oversees all studies conducted at the Center for Scholars & Storytellers at UCLA. She earned her PhD in History & African American Studies from Duke University and is a former faculty member of Wake Forest University's History Department.

-

Matt Puretz, M.A.

Senior Researcher

Matt Puretz (he/they) is a Senior Researcher at CSS. He specializes in connecting creators to evidence-based insights from media psychology, helping them develop content that inspires social impact.

-

Kate Stewart

PhD Student at The Ohio State University

Kate is a 3rd year PhD student at the Ohio State’s School of Communication. She studies how puberty is depicted in media, and the effect that those portrayals can have on adolescent audiences.

-

Aman Johnson

Master’s Student at University of California, Los Angeles

Aman Johnson is a master's student in the MFA Producers Program at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television.

-

Keara Williams

PhD Candidate at University of California, Los Angeles

Keara is a 5th year PhD Candidate at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education and Information Studies where she examines how the community school model supports Black students and advances Black liberation.

Acknowledgements

Special Thanks to:

Funders for Adolescent Science Translation (FAST)

A tremendous thank you to Henry Carter and Anthoney Xie, whose work on data analysis was key to making this project happen.

Thank you to Iziaih Choquette, Christopher Hendrix, Sky Page, Seraiyeh Versai, and Arlena Ortega for speaking at our event and candidly sharing about their lives and experiences.

To our amazing director of special projects, Nina Linhales Barker, and our marketing & development manager, Haidy Mendez, for helping keep this project on track and grounded, along with everyone at CSS who contributed to its success.

Methodology

-

In June of 2025, CSS hosted the Creative Collaboration Think Tank Conference with youth advocates and media industry professionals. The focus of this year’s conference was elevating the voices of systems-facing youth. As part of this initiative, the fellows at the Center for Scholars and Storytellers and our research team designed a survey that was distributed to adolescents across the country. Consisting of primarily quantitative questions, the survey aimed to investigate adolescents’ exposure to systems-facing youth, perceptions of these youth, and the role of media in communicating these stories to young people. All respondents were asked whether they know any youth have experienced homelessness, incarceration, the foster care system, and immigration. When respondents indicated that they did know someone from a system, they were asked about the nature of that relationship - whether the youth was a friend, family member, or someone from their school or community. Respondents were also asked if they have ever learned about each of the four systems through school or community programs. To understand perceptions of systems-facing youth, all respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed that youth from each system were “victims of circumstance” and whether “society does enough to help” each group. The media questions asked all respondents whether they think media impacts how society sees systems-facing youth, if they would like to see more stories on each of the four groups, and what they would like to understand about systems-facing youth.

-

The target population for this study consisted of adolescents across the United States between the ages of 9 and 24. A total of 1,552 participants completed the survey; representing diverse gender, sexuality, and racial/ethnic identities. See below for the full demographics.

Race:

African and/or African American and/or Black 29.8%

Asian and/or Asian American 7.9%

Hispanic and/or Latine 14%

Middle Eastern and/or North African 1%

Multi-racial 4.1 %

Native American 1.4%

Pacific Islander .3%

White and/or Caucasian 39.9%

Prefer not to say 1.2%

Prefer to self describe .5%

Gender:

Female 51.9%

Male 44.5%

Nonbinary 2.3%

Not sure .7%

Prefer not to say .6%

Self describe .1%

Region:

Midwest 22%

Northeast 20.7%

South 40.7%

West 16.6%

LGBTQIA:

Asexual 3.7%

Bisexual 13.5%

Heterosexual/Straight 69.7%

Homosexual/Gay/Lesbian 4.8%

Pansexual 1.9%

Queer .8%

Prefer not to say 4.3%

Prefer to self-describe 1.3%

-

The CSS team contracted a third-party survey recruitment platform, Alchemer, to conduct a survey of 9- to 24-year-olds from across the country. Participants were compensated by Alchemer to complete the survey and were provided instructions on how to access and complete the survey online. Participants under the age of 18 were required to have parental/caregiver consent upon participating in the survey. The survey took approximately 15 to 25 minutes to complete. Survey responses were collected in May of 2025.

-

Once the survey responses were collected, the data were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the overall responses from teens, and regression analysis and ANOVAs were performed to examine the relationship between key independent and dependent variables. The data analysis was performed using the statistical methods software SPSS.

-

It is important to acknowledge some limitations of this study. As with any self-report questionnaire, there is a possibility of response bias or social desirability bias. Additionally, the dataset was not weighted or balanced, meaning some demographic groups might be over- or underrepresented.